(NRC Handelsblad June 16, 2017; for the original version, click here)

(translation Trudo Lemmens)

Message for the government coalition negotiation table

The Euthanasia Law does not provide protection to people with dementia and psychiatric problems, says Boudewijn Chabot. “Silently, the foundation of the law is being eroded.”

Boudewijn Chabot is a geriatric psychiatrist and researcher of voluntary end-of-life choices.

About twenty years ago, I was sitting on the bench for the accused in the High Court. This was ten years before the adoption of the Euthanasia Act, after I had given a fatal drink to a 50-year-old, physically healthy social worker. Judgment: ‘guilty without punishment’. I fought – and fight- for self-determination. However, I am now worried about the rate at which euthanasia is performed on demented and chronic psychiatric patients.

Recently, the third evaluation of the Euthanasia Act, which came into force in 2002, came out. And like the previous evaluations, the tone was positive. “The goals of the law have been realized. All actors are satisfied about the content and functioning of the law.” That sounds all very well, but it’s not. Since this contentment hides problems which the researchers fail to mention.

To understand what has gone wrong, the reader must know the three most important “due care criteria” of the law. There must be: 1) a voluntary and deliberate request; 2. unbearable suffering without prospect of improvement; 3. No reasonable alternative to euthanasia.

The second and third requirements are closely linked because if another solution, such as specialist palliative care, is indicated, the suffering is not without prospect of improvement. If the patient refuses that option, the physician will not be convinced of the “unbearable” nature of the suffering and will not provide euthanasia.

At least as important is what is not in the law. There is no requirement that the disease has to be physical, and the doctor need not have a treatment relationship with the patient. Many doctors and lay people thought this was the case. But such restrictions are deliberately omitted to allow for the development of concepts such as “unbearable suffering without prospect of improvement.”

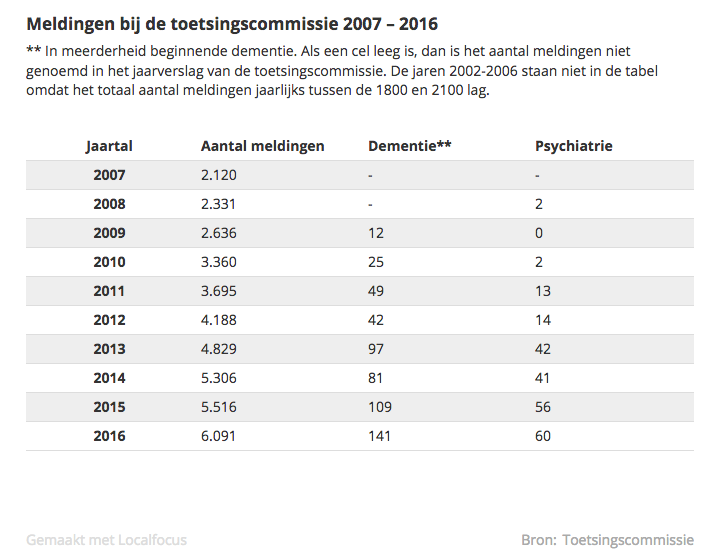

In the last ten years, the number of euthanasia reports has increased from two thousand to six thousand per year. People ask for it more often, doctors are more often willing to provide it, and consultants who assist the doctors give more often the green light. In 2016 the review committee found that only 10 of the 6,091 (0.16 percent) cases was done without due care.

All of this indicates a shift in culture in relation to self-selected dying under the custody of the doctor. Apparently doctors heed the increasing demand for euthanasia in the context of all kinds of nasty diseases, particularly cancer. In and of itself, this increase does not disturb me – even if the number exceeds ten thousand in a few years.

What does worry me is the increase in the number of times euthanasia was performed on dementia patients, from 12 in 2009 to 141 in 2016, and on chronic psychiatric patients, from 0 to 60. That number is small, one might object. But note the rapid increase of brain diseases such as dementia and chronic psychiatric diseases. More than one hundred thousand patients suffer from these diseases, and their disease can almost never be cured. Particularly in these groups, the financial dismantling of care has affected patients’ quality of life. One can easily predict that all of this could cause a skyrocketing increase in the number of euthanasia cases.

Strikingly, doctors from the End of Life Clinic Foundation* are often euthanizing these patients, while as a matter of principle they never treat patients for their illness. By 2015, a quarter of euthanasia cases on demented patients were performed by these doctors; in 2016 it had risen to one third. By 2015, doctors of the End of Life Clinic performed 60 percent of euthanasia cases in chronic psychiatric patients, by 2016 that had increased to 75 percent (46 out of 60 people).

There appears to be a realization that something is going wrong, because the review committee has recently been strengthened with a few specialists in the field of geriatric medicine and psychiatry. However, their vote will be lost in the choir of the forty-five commissioners who are responsible for the current ‘jurisprudence’.

These figures also cannot be found in the annual report of the committee or in the statistical tables of the researchers. For sure, the fact that in 2016 euthanasia has been granted to a total of sixty psychiatric patients is included in the annual report of the review committee. But nowhere in the report is it mentioned that in 46 of these cases, it was a physician at the End of Life Clinic who granted the request. That number you have to dig up from the annual report of the End of Life Clinic. Is this fog purely coincidental?

Cornerstone of the law

Is it still possible to put a break on this development? It won’t come from the review committee, which cannot go back on its ‘case law’. Already back in 2012, at the time of the second review of the law, it became apparent that the review committee no longer discussed whether the due care criteria of “unbearable suffering without prospect of improvement” were fulfilled. The committee members found this difficult to evaluate, as was already apparent from the previous review of the law: “If the notifying physician and the consultant found the suffering to be unbearable, who are we to say something more about it here?”

The interpretation of this cornerstone of the law already came down to what the doctor and consultant accept as unbearable suffering without prospect of improvement.

This is also clear from the reviews. In 2016, the committee found in only one of the 201 cases of euthanasia in dementia and psychiatry that the evaluation had been careless [not in line with due care] because the requirement of “unbearable suffering” had not been met. What problem is this evaluation structure, which costs about four million euros annually, really solving? The researchers fail to answer this question.

Once upon a time, moving to a nursing home or receiving treatment with some medication was still considered a “reasonable alternative” for euthanasia. At least it had to be tried. Many doctors now accept that a patient can refuse a reasonable alternative and that this does not create a barrier for euthanasia. That brake has now also disappeared.

In the Chabot judgment, the Supreme Court had still required “exceptionally great caution” with respect to psychiatric patients. Those words are now trite, because a reasonable alternative to death can now be refused and the committee will still provide its stamp of approval that the euthanasia was done with due care. This has been the case for many years, since already at the time of the previous evaluation of the law the majority of the review committee did not find that doctors were too easily accepting that patients reject a reasonable alternative.

Within the End of Life Clinic, a group culture has emerged in which euthanasia is regarded as virtuous labor

Ethicist Govert Hartogh, who has for many years been a member of the Evaluation Committee, has identified this subtle but steady process of erosion: “The patient suffers unbearably when he says he suffers unbearably and an alternative is not a reasonable alternative if the patient rejects it. In fact, these requirements then add little to the requirement of a voluntary and thoughtful request.”

The erosion of nice words reminds us how it has gone with the abortion law. In order to get abortion, a woman had to be in an “emergency” situation. Soon every woman knew that she got what she wanted if she requested it and rejected any other solution. The Dutch legislature has often been creative in areas of morality, with big words that, after a while, completely lost their bite. Consider the “enduring disruption” that was required for divorce.

The fading of legal requirements does not have to be a problem. Sometimes this leads to an amendment of the law, such as with “enduring disruption.” Sometimes we also accept that the core idea behind the law has shifted to favour self-determination, such as in the case of abortion. The problem is, however, that the euthanasia committee continues to speak of “unbearable and hopeless suffering” in its annual reports, as if these words still really have great weight.

While researchers are pointing to the growing emphasis on self-determination, they fail to mention the erosion of the two other legal requirements. Silently, the very foundation of the law is eroded.

The doctors working within the End of Life Clinic consider themselves at the “forefront” and call the clinic a ‘centre of expertise’. Unfortunately, there is very little expertise in palliative care, for the simple reason that when a patient rejects treatment it is accepted as an expression of self-determination.

In 2016, about 40 physicians working part-time at the End of Life Clinic performed euthanasia 498 times. On average, this amounts to 12 euthanasia’s per doctor, one per month. Within the clinic, a group culture has emerged in which euthanasia is considered to be virtuous labour, especially in severe dementia and chronic psychiatric patients. The fact that the End of Life Clinic also rejects many requests is thereby irrelevant, since many people who do not at all qualify for euthanasia contact the clinic.

What happens to doctors for whom a deadly injection becomes a monthly routine? They are surely well-intended, but do they also realize how they are fanning a smoldering fire that can become a blaze because they fuel the death wish of vulnerable people who are still trying to live with their disabilities?

The End of Life Clinic is now actively recruiting psychiatrists. It justifies this by pointing to the long waiting list. Their task: relieving the unbearable and unrelievable suffering from psychiatric patients through euthanasia. Every time the Clinic is in the news, a wave of depressed patients whose treatments are allegedly exhausted but many of whom have never been properly treated report to the Clinic. Ever since budget cuts turned chronic psychiatry into a diagnosis-prescription business, good treatment has become scarce.

The newly recruited psychiatrists won’t need to enter into a treatment relation with the patient. The evaluation committee has accepted that in the case of severe physical illnesses. Now it has also applied this to incurable brain diseases—without discussing it with members of the psychiatric profession by the way.

Ever since budget cuts turned chronic psychiatry into a diagnosis-prescription industry, good treatment has become scarce.

This has been an overly hasty step. Without a therapeutic relationship, by far most psychiatrists cannot reliably determine whether a death wish is a serious, enduring desire. Even within a therapeutic relationship, it remains difficult. But a psychiatrist of the clinic can do so without a therapeutic relationship, with less than ten ‘in-depth’ conversations? Well …

With dementia there is another concern. The Euthanasia Law has added that a written letter of intent may replace an oral request, while the other due care criteria remain applicable. According to ethicist Den Hartogh, this implies that for a demented patient, two of the three due care criteria disappear—the requirement of a well-considered request and the requirement that reasonable alternatives have to be tried—because they cannot be applicable.

What remains is the requirement that there should be unbearable suffering that cannot be alleviated. But it is often very hard to determine whether there is unbearable suffering in advanced dementia, as five professors of geriatric medicine recently stated in NRC. The personal colouring of ‘suffering’ in dementia plays a major role.

Yet, that uncertainty doesn’t appear to be a problem for the review committee. When a physician and a geriatric specialist note in their report that a person with dementia suffers unbearably, the committee may occasionally ask a question about that, but it doesn’t cause any further problems.

With the erosion of the concept of “unbearable suffering” and the determination that a written consent is the same as an oral request, the door has been opened wide for euthanasia of patients with severe dementia.

Yet, we still face a formidable obstacle in the context of severe dementia: how do you kill someone who does not collaborate because he has no realization of what will be happening? Already in 2012, NRC described how this works. A spouse mixed sleep medication in the porridge of his demented wife before the GP arrived with his deadly syringe. At the time, the review committee failed to mention anything about this assistance. In later cases of euthanasia with advanced dementia, the committee also remained silent about the precise details of the execution.

In 2016, there were three reports of euthanasia of deep-demented persons who could not confirm their death wish. One of the three was identified as having been done without due care; her advance request could be interpreted in different ways. The execution was also done without due care; the doctor had first put a sedative in her coffee. When the patient was lying drowsily on her bed and was about to be given a high dose, she got up with fear in her eyes and had to be held down by family members. The doctor stated that she had continued the procedure very consciously.

Thus, a doctor can kill someone surreptitiously, because you cannot resist after being sedated. If necessary, physical force is used. A large group of doctors called this “sneaky” and published a full-page advertisement, including in NRC, letting our society know that they will not do this.

History repeats itself

In the third review of the law we can find the following remarkable sentence about the surreptitious administration of a fatal drug: “This can in those cases be inherent to the nature of the situation and has not been previously considered a problem.”

The surreptitious administration of medication has previously occurred, but has never been mentioned in an annual report. That is odd, because the committee queries doctors relatively frequently about the medications they administered and judges deviations from the Euthanasia Directive relatively frequently as careless. In a deeply demented person, we are dealing with a morally problematic act: how do you kill someone who does not understand that he will be killed? Remaining silent about the precise way of execution appears very far removed from the transparency that the committee expects of doctors.

The researchers compare this form of cover-up to be “inherent to the nature of the situation”. When it comes to the killing of a defenceless human being, everything that is deemed “inherent to the situation” should be very clearly identified in the evaluation and in the annual report. The review committee has failed in transparency, for five years now. And the researchers smoothen this out.

Would the Public Prosecutor’s Office now take up its responsibility after being laid back about it for fifteen years, and submit the case to the court? Earlier, when the review committee considered in one euthanasia case that due care had not been met for all three legal requirements, the public prosecutor failed to prosecute.

In the context of severe dementia, the following legal questions can only be answered with authority by the Supreme Court: can people be killed surreptitiously? Isn’t that a form of duress, since any possible resistance is being prevented? Isn’t it precisely when we’re dealing with a defenceless person that any hint of coercive force must be avoided?

In the case of the woman who got up with fear in her eyes, the public prosecutor can launch an appeal in the interest of the law. He can then submit the matter directly to the Supreme Court. I think that the public prosecutor will very likely take a wait and see approach. In that case, geriatricians, for whom clarity on this legal question is of utmost importance, can appeal the decision not to prosecute in a court of law.

History repeats itself when it comes to laws dealing with challenging ethical issues. Self-determination around the end of life is for many people as important as in the context of abortion. It is therefore not surprising that the first due care criterion, a voluntary and well-considered request, has gained in importance. And that criterion has pushed the other two due care requirements to the margins. What is astonishing is that in the third evaluation of the law, the researchers still keep up the smoke screen around ‘unbearable suffering without prospect of improvement’.

Where did the Euthanasia Law go off the tracks? The euthanasia practice is running amok because the legal requirements which doctors can reasonably apply in the context of physically ill people, are being declared equally applicable without limitation in the context of vulnerable patients with incurable brain diseases. In psychiatry, an essential limitation disappeared when the existence of a treatment relationship was no longer required. In the case of dementia, such a restriction disappeared by making the written advance request equivalent to an actual oral request. And lastly, it really went off the tracks when the review committee concealed that incapacitated people were surreptitiously killed.

I don’t see how we can get the genie back in the bottle. It would already mean a lot if we’d acknowledge it got out.

(*note translator: The End of Life Clinic (official name: Stichting Levenseindekliniek) offers access to euthanasia to patients whose own physicians have denied their request for euthanasia. For more information on the organization, click here)

My first experience with Doctor Assisted Death was over 30 years ago in Holland. It resulted in a very queasy 24 hours.

Since then I have come to accept the humaneness of euthanasia and I now firmly believe that every person should have the right to dictate their end-of-life; after consultations with family, friends, and other specified individuals.

Canada is a Democracy and not a Theocracy. The Laws and the Church must respect these rights.

LikeLike

If you read carefully the critique by Dr. Boudewijn Chabot, then you should be able to understand that his critique, and the critique of many others who point out some serious problems with the developments in Belgium and the Netherlands, has nothing to do with Theocracy. It escapes my understanding how people simplistically reduce this to a religious vs liberal issue. What he points out goes to core values embedded in every basic human rights code. Since when is discomfort about the use of physical force in the killing of a person suffering from dementia and who physically resists or about the termination of life of a person suffering from serious mental health issues who may not fully appreciate that there are treatment options, an issue of “Theocracy”. Unless Canada wants to abandon its human rights obligations to protect those who are vulnerable from premature death and abuse, it has to take these problems seriously when contemplating expanding its current medical assistance in dying law. Your desire to dictate your end of life is not a justification to abandon the long-standing tradition in Canada (and elsewhere) to protect people who are vulnerable.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you for your response.

1/ My comment on Theocracy relates specifically to Canada, and, I believe that you have an oar in the water.

2/ I suspect that your “the use of physical force in the killing of a person” relates to the, well hyped, video of an elder lady who apparently did not receive a sufficient quantity of the sedative.

3/ Boudewijn Chabot; “This increase alone troubled me not – even if the number of passes the ten thousand in a few years.”, and, “Yet now I am concerned about the pace of committing euthanasia increases with dementia and chronic psychiatric patients.”

An individual’s pain can be physical and/or mental in nature. Hopefully the ‘End of Life Clinic’ in Holland and an upgraded Canadian law will prove successful in provide a benevolent transition for those that cannot presently obtain it.

4/ Tradition as in theology??? You use the word ‘vulnerable’ twice. Vulnerability is a two-edged sword and the patient must be protected from both edges.

LikeLike

Dr. Chabot only met with the 50 year-old, physically healthy social worker to whom he gave a fatal drink 10 years before the adoption of the Euthanasia act four times. If 10 meetings is not a therapeutic relationship, how can four be?

Suffering is brutal and some people want to avoid it with death. But suffering is part of life and a therapeutic relationship involves helping a patient to live with suffering. When doctors, including psychiatrists, are both healers and executioners, even benign executioners, whom can we trust?

LikeLike

Mr. Jackson, it is probably a waste of time but some of your comments are too troubling to let them stand unanswered on this webpage:

Your point 1) Re I have ‘an oar in the water’. What are you insinuating? If you use this expression in its ordinary meaning, you suggest that I am improperly interfering here in other people’s conversation. Since when is an anglo-saxon name needed to legitimately participate in a discussion about Canadian values? And even if I wouldn’t have been Canadian: how would that have mattered with respect to the argument that this has nothing to do with theocracy? Is Canada somehow an island of liberal virtues so that no one from the ‘outside’ can say anything legitimately about this?

Your point 2/ Read Chabot’s article more carefully and with open eyes and mind. He discusses a case reported by a Dutch review committee. The doctor who reported it and who performed the ‘benevolent transition’ admitted the use of force and stated she very consciously overruled the physical resistance by the demented person. And if with the ‘hyped’ video you refer to the documentary highlighted in the other op-eds I translated: if you remain indifferent to what happened there; if you don’t see that there are serious questions about consent; about voluntariness and vulnerability; and if you think we should have no concern about ending the life of a person in those circumstances, then I think we live in a very different moral universe. You seriously want to trivialize this as cases where all the moral issues would be solved if ‘more sedatives’ had been used?

Re 3/ I disagree with Chabot that the mere increase is not a concern. See below in a separate response a copy of a short commentary by Catherine Frazee about what the ‘data’ do not tell us and about how contextual factors already contribute to people’s choices in end of life situations in Canada. I further find it disturbingly superficial when people like you fail to see that there are unique concerns in the mental health context: with regards to capacity, predicting treatment outcomes, the impact on the treatment relation, and understanding how the desire to die is often intermingled with the illness itself. We recognize in Canadian human rights law the need for equal protection, which requires protective measures to be adjusted to the special needs and vulnerabilities of specific groups. It is telling that most people who work in mental health are profoundly concerned about the push by some to treat this as another treatment option, particularly in the context of mental health where it may seriously impact the therapeutic relation.

Re ‘benevolent transition’: this euphemism reflects a naive believe that the medicalization of the end of people’s lives is so inherently more humane and without conflicts. This is not about transition to better health, it’s about transition to non-existence. It is surprising how some people believe that medical transgressions, which are well documented in all areas of medical practice, will somehow not be present when we grant doctors the most extreme power and responsibilities, i.e. the power over life and death. We should also be concerned, as Chabot expresses it, what it does to doctors who perform this very frequently.

Your point 4/ So why is the word tradition per se improper? Tradition as in: human rights tradition, a tradition with its historical roots developed following WWII; tradition as in our long-standing commitment to fundamental rights reflected in the Charter….

As to the need to protect people who are vulnerable: that is indeed explicitly recognized by both the trial judge in Carter and the Supreme Court. They both emphasized that any strict regulatory regime has to balance access to MAiD with the need to protect the vulnerable. MAiD is identified in Carter, and rightly so, as an exception to a ‘traditional’ prohibition to kill people. Indeed, there have been/are countries that trivialize this traditional prohibition. I hope ours will not be one of them.

Yes I use the word vulnerability. For sure, one can argue that people who are vulnerable may have a desire to obtain support in dying. It is a balancing issue. Who is most at risk? And how do we balance competing demands and needs? Is the mere desire to control the precise moment and circumstances of one’s dying in all circumstances worthy of more protection than the need to protect people from premature death (i.e. people who with adequate care would recover or continue to live for a reasonable period of time; people who may be under social, economic and personal pressures; people who may have diminished capacity)? For those who want to control their dying (and it is documented that this is the primary reason why MAiD is sought; nearly all physical suffering at the end of life can otherwise be adequately addressed), we can offer many other forms of support to reduce suffering. For the latter, it’s the choice between being death or alive.

There is nothing ‘a-liberal’ or theocratic about limiting the exercise of people’s rights or the fulfillment of individual demands for the protection of others. It’s embedded in the Charter jurisprudence, including in the Carter case itself. If that would be unacceptable, we’d have to scrap all environmental protection, labour protection rules, discrimination provisions etc.

In short: engage with the arguments, stop simplifying the issues, and certainly stop misrepresenting the debate (either out of ignorance or intentionally) as if all those who express concerns are doing so from a religious perspective and are imposing religious views on others.

LikeLiked by 1 person

ARCH Alert Volume 18, Issue 2. June 21, 2017

http://www.archdisabilitylaw.ca/sites/all/files/ARCH%20Alert%20-%20Volume%2018,%20Issue%202%20-%20June%2021%20%2017%20-%20Text.txt

First Interim Report on Medical Assistance in Dying from the Government of Canada, Commentary By Catherine Frazee, Professor Emerita, Ryerson University

Almost exactly one year ago, Kerri Joffe and Erin Elias introduced readers of ARCH Alert to Canada’s new law permitting Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD). They explained that doctors and nurse practitioners are now authorized to end the life of a patient under strict conditions of eligibility. For their full review of the law and its safeguards, the history of its passage and the role played by disability rights organizations as the law was being debated, go to http://www.archdisabilitylaw.ca/node/1133. Now that the law has been in place for one year, this article will review what we know about how MAiD is being implemented. On April 26, 2017, the Government of Canada released its first interim report on the delivery of medical assistance in dying. This report covers a 6 1/2 month period from June 17 to December 31, 2016, during which time there were 803 publicly reported medically assisted deaths across Canada. An additional 167 medically assisted deaths took place under Quebec law, prior to the passage of our federal law. To read the Government’s complete report go to https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/publications/health-system-services/medical-assistance-dying-interim-report-dec-2016.html. The report provides a very broad profile of who is receiving assisted death in Canada. In Ontario, for example, of 189 deaths reported over a 6 1/2 month period, the average age of recipients was 73 years, the gender distribution was relatively equal, and the proportion of recipients living in urban centres was 75%. Almost 60% of assisted deaths in Ontario during the reporting period took place in hospital, with 34% taking place at home. Persons with cancer, neurological, circulatory and respiratory conditions made up the largest proportion of persons who chose an assisted death. While none of these averages and percentages may be particularly alarming, disability rights advocates have good reason for concern that individual experiences of discrimination and abuse will not be detected when only aggregate numbers are reported. For example, the assisted death in July 2016 of Archie Rolland, a 52-year-old man with ALS, met all of the legal requirements of Canada’s MAiD law. Specifically, Mr. Rolland: * was over 18 years of age, * had the capacity to make his own health care decisions, * had requested and consented to his death, * had a serious and incurable illness, disease or disability, * was in an advanced stage of irreversible decline in ability, and * his natural death was reasonably foreseeable. Canada’s interim report on Medical Assistance in Dying registers Archie Rolland as merely one of 803 total deaths, unremarkable except perhaps for his being 20 years younger than the average. For the much more detailed and alarming story of what led up to Archie Rolland’s assisted death, we must turn to reports published in the Montr‚al Gazette last year, one of which can be found by going to http://montrealgazette.com/news/local-news/life-in-long-term-hospital-unbearable-montreal-man-with-als.

According to this newspaper report, based on interviews and extensive email exchanges, Mr. Rolland had been forced to transfer from a specialized care facility to the regular long-term care ward of a local hospital where staff were not trained to care for patients with complex needs. Mr. Rolland, who was ventilator-dependent and communicated by means of an eye-tracking mouse in his eyeglasses, wrote detailed complaints to hospital administrators and others in a desperate attempt to draw attention to the suffering he experienced as a result of poor care. On one occasion, Mr. Rolland went into respiratory failure when staff failed to suction him properly, and subsequently ignored his ventilator alarm. On another occasion, he was left in extreme discomfort because a caregiver unfamiliar with his needs leaned against the rail of his bed, making it impossible for him to move his head in order to communicate with her. Once, when his mother had too strongly advocated on his behalf, she was banned from the hospital until hiring a lawyer to have her visiting rights reinstated. Although his friends reported that Archie Rolland had “clung to life passionately” for 15 years following his ALS diagnosis, after just a few months of this struggle for good care, he told reporters that he was “suffering too much to live”. He clarified that it was not his illness that was killing him. He was “tired of fighting for compassionate care”. Because Archie Rolland was an articulate and passionate advocate for his rights as a disabled person, we are left with one very detailed and troubling story of how the lack of adequate supports and services can become an inducement to seek assisted death. What we do not know is how many more stories remain to be told about similarly intolerable conditions of living that may have pushed others of the 803 Canadians who have ‘chosen’ assisted death. Archie Rolland’s story helps to illustrate the importance of robust monitoring of medical assistance in dying that goes far more deeply than the government’s interim report. Recognizing that governments must be held to account for failing to meet the critical needs of citizens with disabilities like Mr. Rolland, the United Nations Committee reviewing Canada’s implementation of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) gave particular attention to medical assistance in dying in its Concluding Observations released last month.

To read the Committee’s Concluding Observations go to: http://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/treatybodyexternal/Download.aspx?symbolno=CRPD%2fC%2fCAN%2fCO%2f1&Lang=en.

(ARCH and many other disability rights organizations in Canada made a joint submission to the UN Committee, which can be found by going to http://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/treatybodyexternal/Download.aspx?symbolno=INT%2fCRPD%2fICO%2fCAN%2f24846&Lang=en).

The UN Committee expressed in very forceful terms its concern “about the absence of regulations for monitoring medical assistance in dying, the absence of data to assess compliance…, and the lack of sufficient support to facilitate civil society engagement with and monitoring of this practice”. Among several clear recommendations, it emphasized that persons with disabilities must have access to “a dignified life made possible with appropriate palliative care, disability support, home care and other social measures that support human flourishing”. The Committee also called for collection and reporting of detailed information about requests for assisted death, and the enforcement of regulations to ensure that “no person with disability is subjected to external pressure”. Having accurate and detailed information about the implementation of MAiD is essential if people with disabilities and our allies are to exercise effective vigilance. This is especially true in view of a research study published in January of this year in the Canadian Medical Association Journal. The study concluded that medical assistance in dying “could reduce annual health care spending across Canada by between $34.7 million and $138.8 million”. A report on this research was published in the Globe and Mail and can be found by going to https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/assisted-suicide-could-save-canada-up-to-138-million-a-year/article33701475/.

To continue to live until the time of his natural death and to do so with dignity, comfort and satisfaction, Archie Rolland required skilled, consistent and appropriate care. At a time of increased pressure upon care providers to reduce costs, disability rights advocacy is a critical line of defence to ensure that medical assistance in dying is not normalized as a ‘solution’ to problems of injustice, neglect or inadequate care. ARCH supports the 2017 recommendations of the UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities with respect to MAiD and will be working closely with other disability rights organizations in Canada, and with the Vulnerable Persons Standard community to ensure that the Government of Canada moves quickly to mobilize a national system of monitoring and reporting of MAiD data that is both robust and broadly accessible. To learn more about the Vulnerable Persons Standard, go to the June 2016 issue of ARCH Alert at http://www.archdisabilitylaw.ca/node/1133 or go to http://www.vps-npv.ca/. In a future issue of ARCH Alert, we’ll discuss legal challenges to the law currently before the courts. Two individuals with disabilities in British Columbia and two in Quebec are arguing against the law’s requirement that a person’s natural death must be “reasonably foreseeable” in order to receive medical assistance in dying. To see how Canada’s national media has reported on these cases, go to: http://www.ctvnews.ca/health/second-plaintiff-joins-court-challenge-of-assisted-dying-law-1.3424823 and http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/assisted-dying-quebec-canada-legal-challenged-1.4160016.

In another case, physicians who conscientiously object to MAiD are challenging the Ontario requirement for doctors to provide effective referral to patients who request an assisted death. To read more about this case, go to https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/christian-doctors-challenge-ontarios-assisted-death-referral-policy/article30552327/

We’ll also provide an update on three studies currently underway at the Council of Canadian Academies, considering issues related to providing MAiD to persons younger than 18 years of age, persons whose natural death is not reasonably foreseeable but who request MAiD because of a mental health condition, and persons who are no longer capable of expressing consent but who have earlier indicated a request for MAiD by advance directive. For details about these ongoing studies go to http://www.scienceadvice.ca/en/assessments/in-progress/medical-assistance-dying.aspx.

As the limits of Canada’s MAiD law are tested and challenged, our diverse community of people with disabilities will have to grapple with difficult and potentially polarizing questions. As we debate about values and rights that are deeply personal and have profound consequences for our community, it will be crucial to have reliable and complete information as the basis for our discussions. Medical Assistance in Dying remains a difficult and controversial topic for all Canadians. If you have questions or concerns arising from this article, you may contact the author at cfrazee@ryerson.ca or ARCH Disability Law Centre at archlib@lao.on.ca . Both are committed to open and respectful dialogue.

LikeLike